|

THE NEW TRANSSEXUALS Terre Thaemlitz DJ & Producer

George Petros: I CAME TO KNOW YOU FROM YOUR WORK ON INSTINCT RECORDS. IT WAS THE BEGINNING OF AMBIENT MUSIC — VERY EXCITING TIMES. TELL US WHAT THAT MUSIC WAS, AND WHY, AND ALL THAT — Terre Thaemlitz: My first album on Instinct, Tranquilizer, came out in ’94, the next one, Soil, in ’95. In 1993, there was New York’s first all-Ambient event called The Electric Lounge Machine. I’d DJ there. It was in the Meatpacking District, on 14th Street. That event, for me, was really special because it was an Ambient event that wasn’t strapped onto the Chill-Out room at a Techno party. Like at The Limelight and those events, I always felt they were really super-Straight, and the only women who were there were there with their boyfriends. It just wasn’t an interesting thing; none of that Techno stuff was interesting. ’93 was the breakpoint between Techno and House. You have this moment where they collided in New York. I think the epitome of all that was Moby’s Go EP. It’s the very first one. But then he came out with Go remixes and suddenly it was all very Limelight-style Techno. I SEE — Terre Thaemlitz: So that EP, for me, was the pinnacle of Deep House and Ambient — but not into this super-Techno sound. I really like that sort of stuff. The Electric Lounge Machine was the only place I’d ever DJed after being fired from Sally’s a few years before that. SALLY’S WAS A TRANSGENDER CLUB, RIGHT? Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah, it was basically like a Puerto Rican and African-American sex-worker type of club. It was on 43rd Street at The Carter Hotel. They had a big ballroom and some of the girls had rooms and they’d take their johns there and stuff like that. So, it was a lot of Straight clients — you know, Straight-identified guys — and a lot of working girls. WHAT DID YOU SPIN THERE? Terre Thaemlitz: I was playing Strictly Rhythm instrumental stuff, and early Emotive and Rhythm Beat and that sort of stuff. Basically instrumental, minor-label stuff mostly from New Jersey and the Lower East Side. This of course didn’t really go over so well. You know, people remember the scene and you see all these great documentaries with really great music. But it was really hard to find places where you could play a lot of instrumental House stuff. Everybody was into the wailing diva stuff. You had to mix that in a lot, which I didn’t like to do. That’s why I’d always get fired from places. WHAT WERE YOU SPINNING AT THE ELECTRIC LOUNGE MACHINE? Terre Thaemlitz: That was kinda an asexual party. It was really like a No Vibe thing. The best thing we could do at that party was to put people to sleep. So, whoever could put the most people to sleep during their DJ set was the best person that night. That was really kinda the big thing for me. You know, ’93-’95 — it was really about putting people to sleep. That was my goal. LIVING UP TO THE NAME AMBIENT THERE — Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah, yeah. You asked what it was about, and what it was about was trying to get away from spectacle-based music and, of course, as a scene it kind of backfired. It ended up with DJ Spooky as the superstar of the scene, or you had The Orb doing concerts with drummers and bassists. I mean, everything became about spectacle and identity and celebrity when, in fact, the thing that was interesting to me was the allure of doing something anti-spectacle and doing something that was very much about anonymity, and complicating the relationships between environmental and melodic sound. You know, trying to get away from the tyranny of music. It’s a conventional early-Brian Eno model of ambience filtered through Haruomi Hosono’s Globule manifesto. Eno’s concept was more Deep Modernist and based on a model of nausea and isolation, and then moving that into a dance-floor environment — TELL US ABOUT HARUOMI HOSONO. Terre Thaemlitz: He’s the founder of The Yellow Magic Orchestra. They were the classic Japanese Techno Pop band. They were really big in Japan but of course, filtered through the American Rock & Roll distribution system, they were totally bizarre and hard to find. He’s not at all Transgendered-identified but he would play with these images that were collages of his face with Fifties female movie stars and stuff. They were done in a way that was not about pleasing aesthetics — more a kind of chop-up model of Transgenderism, so I really liked it. I kinda modeled myself after him — his idea of producing in a lot of different genres, and each of these genres metaphorically relate to identity and so, the idea of producing in a lot of genres is a way of trying to critique, and step away from, the model of the singular-artist identity. Getting away from that, and reducing music to a series of procedures that have social functions, rather than this from-the-heart thing. INTERESTING. REGARDING PUTTING PEOPLE TO SLEEP — WHAT WOULD YOU PLAY? Terre Thaemlitz: The Ambient style at that time was really, really conventional and traditional in that it took Muzak and Jazz and sound-effects records and weird electronic records and Industrial Ambient and soundscapes and anything that was a relaxing quiet sound but not trying to be New Age-y or anything like that. It was like layering. We would have three or four turntables going at once. Repeating them over and over — and kinda creating loops on turntables. INTERESTING — Terre Thaemlitz: There were really a lot of men in the scene. There were very few women DJing. It was very much a boy kind of thing — but it wasn’t this hard Techno Straight scene. People were a little bit older. HOW ABOUT THE TERM “ANDROGYNY” AS IT APPLIES TO THESE CLUB SCENES — Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah, I think it was Androgynous, but in the way which Androgyny falls towards the male Heterosexual normative. It wasn’t a blatant Androgyny that then became something that sets gender and sexuality into question. It was more the kind of conventional neutrality under a Hetero-normative system. So, in terms of sexuality, there weren’t interesting things going on at the events themselves but I think that the idea of trying to get away from the object of music, and the melody, and getting towards more vague open models for sound, was a metaphor for more open models of identity — which included models for gender and sexuality. WERE YOU A TRANSGENDERED PERSON BACK THEN? Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah, but for me Transgendered doesn’t mean dressing in Drag all the time. I was identifying as Transgendered at that point. Before that I had identified as Queer in sexual terms. If I had to identify, I’d identify as Transgendered rather than male but yeah, back in the Nineties, by the time I was at Sally’s, I was identifying as Transgendered. The scene at Sally’s was dominated by Transsexuals. For a person like myself, who is not interested in surgery or hormone therapy, there was a lot of pressure to dress and look a certain style that I just couldn’t. So, I don’t think most of the people at Sally’s even knew that I was Transgendered-identified at that time. I was in the closet to the Transsexuals at Sally’s and while working my day job as a secretary, I was closeted in the more conventional way of putting on a suit and tie to look like a proper gentleman or whatever. So I had these dual closets and didn’t feel comfortable in any space, really. But for me that’s what I think Transgenderism is really about in the end — Transgenderism being the larger umbrella category, and Transsexuality is one segment of Transgenderism. YOU’VE SAID THERE WAS PRESSURE FROM THE PEOPLE WHO UNDERWENT HORMONAL OR SURGICAL ALTERATIONS — Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah — There’s a hierarchy within Transgendered communities and Transsexuals clearly reign at the top, and messy homemade Drag Queens ranking at the bottom. I was someone who could be more in the middle — my style of Drag was not trying to be spectacular at all. I was just trying to pass in a normal way, be kind of invisible. Back then, I was not being campy, not being glammy or whatever. That was also an extension of how I approached music. Putting people to sleep, rather than entertaining them and trying to get them energized. When I went out dressed as a woman, I was in my twenties and I was more able to pass, as long as I didn’t speak and people didn’t hear my voice, and I would basically go somewhere and lurk. Rather than trying to get attention, I’d try to be kind of quote-unquote normal. INNOCUOUS, PERHAPS? Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah, just going somewhere and getting a drink, standing in the corner even when I dressed in male clothing. I don’t drink alcohol. I don’t do drugs and that sort of stuff. So I didn’t have this social entry into the scene that other people did and I didn’t have the relaxants or whatever. So, I was always taking everything in a very sober and anti-transcendental way, from the Marxist perspective. WERE YOU LOOKING FOR LOVERS OR WERE YOU JUST THERE TO HANG OUT? Terre Thaemlitz: Kinda both, but not really. I never had pick-up skills or luck with dating or anything like that. I wasn’t into the whole cruise scene. I also have problems with male aggression in the Gay cruise scene. So it was kinda complicated in that sense. And then, of course, the way people fetishize you if you’re dressed in Drag — they suddenly think it’s all about some sort of kinky pleasure. For me, clothes — whether I’m dressed as a man or woman — are totally oppressive. They’re totally not fun at all. It’s not like I got dressed up and felt sexy and felt good. Not at all. The same way that when I dressed as a man — I feel that both of these gender patterns around clothing are equally oppressive and ascribe to the same systems of patriarchy. I don’t find liberation anywhere within that system. I SEE. Terre Thaemlitz: So of course, when people see you in a dress, they change the way they talk to you. “Oh, girl, you look fabulous,” and all this sort of stuff. It really becomes about their performance around the person in Drag, rather than their trying to connect in any serious way to someone who happens to be Transgender. I think that’s one thing that pushes people to try and look for resolution through physical therapy. You know, hormones and surgery and stuff. In a way, it’s like trying to take things to the next level so that you’re no longer treated as a fetishist freak or whatever. I can sympathize with that. DID YOU EVER CONSIDER HORMONES? Terre Thaemlitz: I did, but it’s never been something that I’ve had the finances to think about seriously. I’ve never even had the finances to do something like hair removal, you know? The processes and models of beauty are not really things that are meant to sustain one through a lifetime. So I was very concerned about, how can one possibly maintain the image they feel comfortable with throughout a life where our bodies are constantly changing? While at Sally’s I worked with some older first-wave Transsexuals in their sixties and seventies, so I also had that experience of seeing the effects of time on the Transsexual body. Of course, you also have to think about the effects of hormones on the body and the side effects and all this sort of stuff. For me, economics, aesthetics, technology and risks outweighed the physical discomfort of being as I am. WHERE WAS THE TECHNOLOGY THEN, IN RELATION TO WHERE IT IS NOW? Terre Thaemlitz: It seems that access is a lot better now in terms of people simply having more options on how to get hormones and treatment. Also, regarding surgery, the aesthetics around how the procedures are performed and also the quality and safety of the implants seems to be improving. A lot more attention is being given to F-to-M procedures than in the past, when everything was only M-to-F. You’ll find other people who will be much more able to talk to you about stuff in technical detail. Because it’s still not an option for me, both in terms of choice and economics. GOTCHA. Terre Thaemlitz: I don’t want to preoccupy myself with something that’s not gonna happen. I SEE. IN THE PERFECT WORLD THAT YOU ENVISION, WHAT WOULD YOU BE IN RELATION TO WHAT YOU ARE NOW? WOULD YOU BE THE FEMALE VERSION OF YOURSELF? Terre Thaemlitz: It’s less about what I would be, and more about who society would let me be. I think that the way in which patriarchies around the world — and I’m saying patriarchies with an “s” because there are very different types of patriarchy — the dominance of patriarchies around the world totally dominate everyone’s sexuality, gender relations and interactions on so many different levels that for me, it’s not really an issue about individual choice, about how does one person become something. For me, it’s more about the process of, how do we un-become? How do we distance ourselves from the patterns of domination that are indoctrinated into us from a very early age? Depending on what toys you’re given — and then if you actually choose to play with the toys that are appropriate for your gender or not, appropriate clothes, and people’s reactions to that — how you either change to conform to what people expect or you resist them, and why you resist them and do the opposite. And usually what you end up doing is the opposite, as opposed to something that’s more complex and interesting. I THINK THIS IS THE LIMITATION TO MOST TRANSGENDERISM — IT’S KIND OF PREOCCUPIED WITH PATTERNS. ONE OF THE GREAT PROBLEMS WITH TRANSGENDERISM IS THAT IT SHOWS HOW WE AS PEOPLE LACK IN IMAGINATION. Terre Thaemlitz: The patterns that have a tendency to dominate Transgendered communities still tend to be the conventional patterns that dominate society in general. It’s just a different relationship between the body and power. People tend to forget that Transgender people, as with Lesbians and Gays, have no more imagination than anyone else. A MATRIARCHY REPLACING A PATRIARCHY, FOR EXAMPLE, WOULD SIMPLY POSE A SIMILAR SET OF RESTRICTIONS, I WOULD IMAGINE. SO, IS THERE AN ACCEPTABLE BLEND — Terre Thaemlitz: We don’t live in a world where we can switch things. I don’t think we have enough experience with matriarchy to know what would happen. Of course, I’m not talking about inversions of power — especially ones that revolve around preserving a kind of binarism of male and female genders. Although most people tend to fall biologically closer to what we would identify as male or female, there are a lot of cases in-between, both physically and psychologically. We have a lot of pressure to push ourselves to either be Black or White, male or female — of course I’m also talking about traditionally male- and female-identified people, people who feel they are biologically male or female. I still think a lot of bodies fall into gray areas, you know? Then it becomes, how do you actually define a male body or a female body? ONCE YOU DEFINE IT YOU CAN ALWAYS FIND SOMEONE MORE MASCULINE OR MORE FEMININE, MORE MALE AND MORE FEMALE. SO, ALL OF THESE GENDER THINGS FALL APART IN THE END. Terre Thaemlitz: I’m not interested in hypothesizing a matriarchy or talking about, like, “Oh, wouldn’t that be liberating?” That’s why I’m not interested in answering directly your question about ideally what would happen. Ideals and dreams are so poisoned and polluted — I wish to escape the dominations. It makes no sense to talk about it because once contexts do change, then of course the dreams themselves change and no longer become desirable. So, for me, that sort of talk doesn’t amount to anything in a strategic way, in political terms. The yes-we-can attitude is totally pointless in the end because it’s diverting attention away from addressing — with urgency — what can no longer be tolerated today. Instead, it puts all that energy into, “What would we like to happen? Where do we want to see ourselves go?” It all enters into a fantasy that is polluted by the oppression of the moment. You lose sight of your own context when you start focusing on those ideals of where you want to see yourself going. I have that attitude where I prefer to not focus on ideas of physical transitioning — it’s hardship rooted in one’s oppression. If there are other ways for me to mediate my existence without having to undergo the life-long regimens those systems currently require — I think maybe it affords me other options. All my money isn’t going into treatment. WHAT’S YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER TRANSGENDERED FOLKS? Terre Thaemlitz: The Transsexual people that I’ve known mostly have been male-to-female. In the end, they always talk about how I should start taking hormones — and when I explain that I’m not interested in that they’d say, “Oh well, give yourself two years —” or “Wait five years” or whatever, you know? It’s like they can’t believe it, you know? In a way, it kind of makes you incomplete, from the Transsexual perspective, if you refuse treatment. It’s kind of like being sexually Queer, rather than Gay. You have the Gay men who will tell you you’re still in the closet because you’re fucking women and you have the women who are saying, “Oh look, you’re a fag. Get away from me!” People find it difficult to accept those who don’t conform to their own identity system, especially when you live under an identity system that requires so much energy and effort to become something. Then it becomes hard to imagine others who wouldn’t need to do the same. I SEE. Terre Thaemlitz: That’s why the Transsexual community often looks with a lot of suspicion at other types of Transgendered people. Of course, I can understand why they might resent the fetishism and campy S&M fetish image, and people just kind of joking around and being into costume play or something like that. I hate that, too. I guess a lot of the people that I’ve gotten along with the best have been Intersex people. TELL US ABOUT THEM. Terre Thaemlitz: Unlike Transsexuals, the Intersex people I’ve met don’t have expectations and hopes rooted in the medical industry. They’re much more skeptical of the industry, especially when you’re talking to people who have been mutilated at birth. Of course, that sets up a lot of skepticism towards the medical industry. I have to say, I lean on that side. I feel that the aesthetics of it — about how to develop the body as a Transsexual — are very much about helping people to conform to a particular model of Hetero-sexist beauty standards. For me, that’s a problem and I know it’s a problem for a lot of Transgendered people too, even for a lot of Transsexuals. I’ve never met a Transsexual person who truly believed they were becoming a man or becoming a woman except in terms of appearance and passability. It’s difficult to discuss these things without using generalizing language — I want to be clear that I’m not lumping all Transsexuals into one group. BUT REGARDING INTERSEX INDIVIDUALS — Terre Thaemlitz: Okay, I was talking about Intersex people, like being born with ambiguous or multiple genitals, and often having some sort of medical experience in their youth. Often very soon after birth, or at a young age, going through operations and usually being told they have cancer or something, when in fact the doctors are removing ovaries or undescended testicles or something like that. So, Intersex people of course have very complicated relationships with the medical industry and the ones that I met don’t trust the industry. Whereas most Transsexuals tend to look towards the medical industry as a place to find a resolution to a gender crisis. I’ve also met some people who stopped halfway. INTERESTING. Terre Thaemlitz: For example, I knew someone who was a man who just did the facial feminization procedure, because men tend to have a kind of more protruded eyebrow bone. So they kind of shave the skull over the eyes and then usually put in chin and cheek implants, or something to make the face look more feminine by conventional standards. Usually you’re taking hormones and maybe doing facial feminization, then maybe you do breasts and finally maybe you then do your genitals. So, it’s kinda like a step-by-step procedure. People who stop after the facial feminization look clearly Androgynous. The person I knew felt that the orientation of the medical industry pushes towards a very particular model of physical appearance, the destination of which she was not happy with — of course the medical procedures are about helping people conform to a quote-unquote normal life. The main reason she stopped was that she felt that the social systems around the body she was transitioning into still didn’t make her feel comfortable and didn’t resolve her initial discomfort with her body. She felt like, in a way, to un-become male or female was more helpful than to un-become one and become the other, in terms of appearance. I want to be very clear that when I’m talking about these things, I’m not trying to generalize the experiences of all Intersex people, of all Transsexuals, of all the different types of Transgendered people. I’m just talking based on the limited interactions and experiences that I, as a Transgendered-identified person, have had. WELL, THAT’S JUST WHAT WE’RE LOOKING FOR HERE — YOUR PERSPECTIVE. Terre Thaemlitz: Back to Intersexuality — I do think most people who had medical procedures performed on them in childhood and infancy would have preferred to have had the option of seeing what their bodies might have become otherwise. ARE THEY ESSENTIALLY MUTILATED FROM THESE SURGERIES? Terre Thaemlitz: In private ways. This is the kind of thing that would come out and interfere with developing interpersonal relationships. It doesn’t necessarily mean something that would be obvious to a person walking down the street — BUT A LOVER OR A POTENTIAL LOVER WOULD KNOW RIGHT AWAY — Terre Thaemlitz: If so, then it suddenly becomes very complicated. Because usually Intersex people are encouraged by their parents and by the medical industry and education systems to either play the role of a boy or a girl, right? RIGHT. Terre Thaemlitz: So, depending on whether they, as adults, decided to embrace or reject that conditioning — that would affect how they would interact with other people. I think within the Lesbian and Gay community there is a bit more openness about it. Especially within the Lesbian community, I think. There’s much more flexibility around concepts of sexuality in the Lesbian culture than there is in the Gay male culture, I find. IS THAT SO? Terre Thaemlitz: I think that playing on a kind of feminine ambiguity that also at times can be masculine tends to be where most of the Intersex people that I meet fall into. That had to do with where they felt more accepted in terms of the other people around them. Obviously if you’re Intersex, it’s a very rare situation and outside of support groups or things like that, it’s not very likely you’re going to run into other people with the same identity and even if they are Intersex, it can be a completely different condition. So, it creates a different type of solidarity. HOW IS IT DIFFERENT? Terre Thaemlitz: When you’re talking about identity politics and communities that revolve around gender identity, you’re usually talking about people rallying around a target body or a target series of actions et cetera. So, for example, within the Transsexual community, there are particular types of bodies that are determined by the limited number of procedures available. Even though procedures are more numerous today than they were before, still they’re very limited in terms of outcome — but people are moving more towards a body-commonality. It’s the same thing as people just coming together as members of a certain community — whatever. I mean together around a singularity. Women Power. Black Power. Gay Power. But within the Intersex community, many of them have different physical conditions — so even when you get many Intersex people together in one room, it’s a gathering that’s not rooted in a commonality of body or a kind of coming together. If there is any sort of connection, it’s around the inability to identify sameness. It’s a connection of experience around the body, and not a connection focusing on the body itself. NOW, THIS IS A RARE GROUP THAT WE’RE TALKING ABOUT HERE — Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah. Some support groups are really organized against the medical industry, where others are actually facilitated through the medical industry.

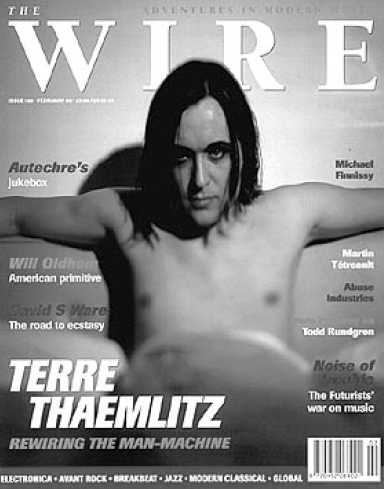

ON A DIFFERENT NOTE — TELL US ABOUT THAT COVER SHOT OF YOU ON THE WIRE. Terre Thaemlitz: Well, what happened was, they finished the photo shoot and I was dressed up. We’d spent the day doing kind of campy pictures. I wasn’t really comfortable with it because, for me, the experience of being Transgendered and being Queer is very much about violence and bashing and closets and traumas and all this non-celebratory stuff. So, I was taking off my makeup and at a point when I looked kind of battered I came out and said, “Start taking my pictures now.” So he did some facial close-ups and then we did that one on the bed. He posed me like that. I thought it was too Rock & Roll for my taste, definitely. We also did one in which I was wrapped in plastic and dumped at the roadside ]as a corpse or something. SOUNDS LIKE QUITE A SHOOT. Terre Thaemlitz: We have these pressures — how to perform and how to be represented. It’s not like the photographer was trying to do something and I was so unwilling to cooperate. I’m trying to help them do their job and they’re trying to show me in the best light they can, from their perspective. There are always these kinds of pressures to perform in a certain way, around what the dominant model of Transgenderism is. What does it mean for a man to put on a woman’s clothes? — and that sort of thing. And basically, if you’re not Transsexual, that’s all you are, you’re either a man in woman’s clothes or a woman in man’s clothes. BACK TO SQUARE ONE. Terre Thaemlitz: I think people usually lean towards conventional models, where it becomes very much about parody. So, the typical behavior that one imagines for a Drag Queen, for example, is being campy, loud, outrageous and kind of flaming. If you think about the typical behavior of a woman who’s cross-dressing as a man, like a Drag King, then typically you’re going to imagine somebody who’s trying to be a little bit street butch and macho, aggressive, lowering their voice — So, we have these expectations of how people should perform before we even meet them, right? Whether you’re in Transgender communities or not, we have these sorts of images. I think it’s usually seen as a kind of parody of true gender, and that’s also part of the humor of it and part of the way for people to deal with it, too. If you can reduce everything to a bad joke, then you don’t actually have to worry about it becoming a serious critique of anything. So humor makes life easier for Transgendered people, as well as the people around them. Everybody laughing together, rather than some laughing at one. That also eases tension and minimizes risks of violence. If you’re playing the role as expected — there’s enough risk already, you know? COULD YOU TELL OUR READERS ABOUT THAT RISK? Terre Thaemlitz: They can find out for themselves just by going to a store and trying on clothes for the opposite gender. I really think that once a year, everybody should be required to cross-dress — and not as a Christopher Street parade-type of festival day, but I mean in ordinary life. They should have to go to work. They should have to go out and buy groceries. They should have to go to the bank. They should have to interact with people at restaurants. You know, do everything that they would normally do, but cross-dressed. I think that’s the only way to understand some of the challenges faced by Transgendered people. But a lot of the way people treat you differently happens before you even reach a Transgendered or Queer identity. I mean, people tend to be zeroed out and bashed in elementary school. For me that was certainly the case — being picked out and Gay-bashed and fag-bashed, being the girly boy and all this stuff at a time way before I had any sense of my own sexuality. That’s why my model of sexuality is so critical of both Heterosexuality and Gay and Lesbianism — because I really see them as part of the Heterosexual and Homosexual binarism, and not something natural. It’s a very constructed paradigm for me, and Gay Pride is not actually about a more open model of sexuality. Really, I think all sexuality boils down to people wanting to touch warm wet places. I don’t really think the body is so discriminating. But of course from a very early age we’re conditioned into certain things and we also have experiences with people of different genders that create biases and traumas in our ability to feel comfortable or uncomfortable around them. So all these things play into sexuality. DO YOUR THOUGHTS ON THIS AFFECT YOUR CHOICE OF LOVERS? Terre Thaemlitz: Yeah, I think absolutely. Basically I’m someone who, if I have to identify my sexuality, I’ll identify as pansexually Queer — and that’s a kind of resistance to both Heterosexual and Homosexual identification systems. Certainly, having a youth spent with a lot of aggression and violence coming from boys and men affected my ability to trust and be intimate and close to men. So, my sexual-object choices tend to go towards the feminine, the Androgynous and women, you know? So then, because I have a cock, people say, “Oh, you’re Straight” — but that’s actually not Straight. If you go out with Heterosexual women and they find out that you’re Transgender-identified — or if you say you don’t identify as Heterosexual — then right there you’re instantly not Heterosexual anymore and open to rejection and bashing. Many women carry a trauma about “fucking Gay men,” or “finding out their boyfriend is Gay,” although you would think accomplishing the sex act itself would deconstruct those categories and betrayals. It absolutely does not — inexplicably, to me. For me, sexual identities really come out of life experience, and not orientation from birth. I don’t feel anything within me springing from a natural well. I feel like my experiences with being bashed and stuff have de-essentialized my sexuality and my gender at the same time those identities were being constructed. I felt that I was forced to become something before I’d reached an age where these were questions one would actually want to make decisions about. It was only violence that snapped me out of the trance, you could say. And that’s nothing to romanticize or turn one into a hero. It didn’t build character. It destroyed it, for sure — although it may appear otherwise. HOW WOULD YOU HAVE BEEN DIFFERENT IF THE WORLD STEPPED BACK AND SAID, “TERRE, WE’RE ANXIOUS FOR YOU TO DO YOUR THING — ”? Terre Thaemlitz: I don’t think that’s a possibility, at all, in any context or time. So, for me then, the question is again, not about trying to think about what one might become. It makes no sense to ponder that. It’s more interesting and important and urgent to think about the disastrous things that happened in real life, that actually transform and affect how we are, rather than to fantasize. What we desire or are capable of envisioning is always rooted in our experience and how we filter and imagine the world around us, as it’s been absorbed both through cultural conditioning and subjective adaptation. Obviously my views and my approach towards things are very affected by Western analytical methods, also very affected by American ideals around models of democracy. Even if I am very critical of, and rejecting, a lot of those ideals. Even when we reject things, we’re operating in relation to them. So, the monk who isolates himself in a cave is still spending every day in reaction to what he left behind. I think this is also something that follows Transgendered and Transsexual people through our lives. It’s also why I try not to buy into — both literally, in terms of money, and ideologically — to buy into these systems to a degree that I have to have faith in them, that I have to have belief that they’re actually something that will help me. In the end, I prefer to have a critical perspective on everything, rather than to allow myself to be duped in any way. I’m duped anyway. It’s just about damage control. ~ |

||||||||||||||||